Though anti-truck advocates would like you to believe otherwise, truck emissions have been rapidly decreasing in the past few decades. New truck engines produce 98% fewer particulate matter and nitrogen oxide emissions than pre-1990 models. Sulfur emissions have been reduced by 97% since 1999. Still, there is more work to be done in order to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by the middle of the century. In November 2018, the Energy Transitions Commission released a report with analysis and suggestions for achieving zero emissions.

Though anti-truck advocates would like you to believe otherwise, truck emissions have been rapidly decreasing in the past few decades. New truck engines produce 98% fewer particulate matter and nitrogen oxide emissions than pre-1990 models. Sulfur emissions have been reduced by 97% since 1999. Still, there is more work to be done in order to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by the middle of the century. In November 2018, the Energy Transitions Commission released a report with analysis and suggestions for achieving zero emissions.

A decent amount of reduced emissions will be driven from market-based solutions. For example, as supply chain logistics become more efficient, emissions can be reduced by 20-30%. This will most likely be on the low end, as it relies on modal shifts to rail or shipping. These modal shifts sound nice on paper but are not nearly as practical in the real world as academics would have you believe, as neither ship nor rail can deliver freight to your house or business. That said, model shifts can work as a substitute for some long haul truck trips, though that would necessitate investments in warehousing and parking facilities (which can be very green if done right) which the report should have discussed as it highlights the issues with modal shifts. Of course, the elephant in the room is the increased demand. The below table projects the freight explosion projected over the next 30 years.

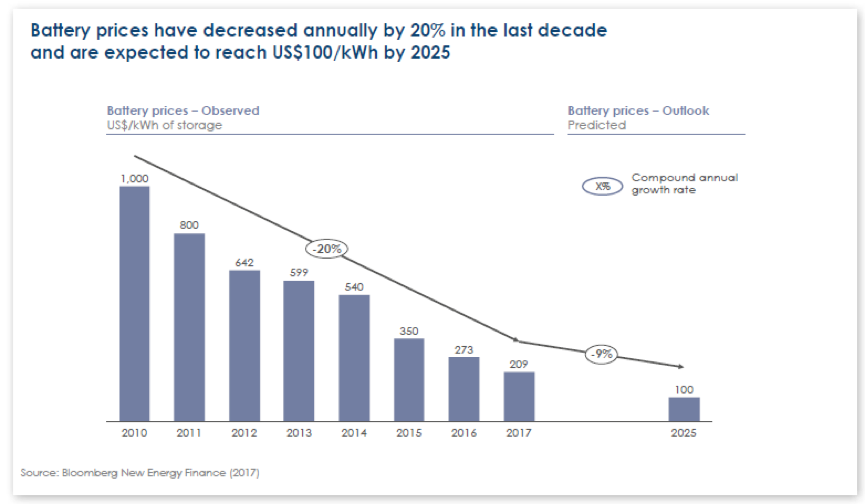

By 2050 it is almost guaranteed that battery charged electric vehicles will be the industry standard as the cost of such vehicles will no longer be prohibitive, the necessary infrastructure will be in place, and older model trucks will have cycled out by this point. The question becomes bridging the gap for the next 10-15 years. Increased efficiency of internal combustion engines as well as improved aerodynamic and tire design is expected to reduce emissions by 30% by 2030, at which point it is expected that electric vehicles will be ready. The expectation is that electric trucks will be cost competitive for short-haul urban areas by the early 2020s, and cost competitive for long-haul by the mid-2020s to early 2030s (see below).

The private sector seems to agree with this analysis as companies such as Tesla, Nikola, Daimler, and Volvo are aggressively working to bring electric and hydrogen powered trucks on the road.

The report believes that “a long-term switch to battery electric vehicles will impose no additional ownership costs, since the full cost of BEV purchase and lifetime operation will, by 2030 be less than the cost of diesel or biofuel ICEs, EVEN IN SITUATIONS WHERE NO EXCISE DUTIES OR CARBON PRICE ARE IMPOSED.” This is a crucial point. In this situation, market forces can reach the desired goal without increasing costs to industry and consumers: a win-win-win. This will, however, require investments in new infrastructure which will have to come from the government (or at least partnerships with the government). Unfortunately, many local governments such as New York’s are far more interested in imposing unnecessary and regressive taxes that will only serve to increase costs on consumers and businesses rather than investments in the infrastructure needed to achieve zero emissions.

Leave a Reply